Dark & Stormy*

Cocktail, or highball? It’s really the latter; the drink really only has two ingredients: dark rum (here, Sailor Jerry Spiced Rum) and ginger ale, with more ale than rum. Garnish is a lime wedge.

There’s not much to the drink, but as a pre-dinner reviver, this one really hit the spot.

I’m not a big fan of flavoured rums, but on a fine, sunlit evening in St Ives in the best fish restaurant in the south west, the Porthminster Café, it really was a great pre-dinner drink.

* Naming note: I have spelled this drink with an ampersand. The original Dark ‘n’ Stormy recipe is protected by trademarks, filed by the rum company, Gosling’s, who invented the original drink, using only their Black Seal rum & a particular Bermudan brand of ginger beer (although they have recently changed to their own). If you’d like to know why, then an article in the New York Times will enlighten you.

The Aviation

The Aviation is a cocktail I had wanted to try making for a while; I liked the delicate blue colour it always seems to have, and the rather unusual collection of ingredients (gin, lemon juice, maraschino & creme de violette – although the last seems to be optional in many recipes).

The Aviation is a cocktail I had wanted to try making for a while; I liked the delicate blue colour it always seems to have, and the rather unusual collection of ingredients (gin, lemon juice, maraschino & creme de violette – although the last seems to be optional in many recipes).

The recipe is a variation on a sour – the gin is given a kick with the addition of lemon juice, sweetened with the maraschino liqueur and given a little colour and flavour by the dash(es) of Creme de Violette.

Proportions – the classic recipe (using a jigger/pony measure):

1 jigger of Gordon’s gin

1/2 pony of lemon juice (see below for thoughts on this)

1/4 pony of maraschino – I used Briottet‘s version, marasquin

Dash(es) of creme de violette – Bitter Truth‘s violet liqueur

Glass: 3oz Martini glass

Method: Put all ingredients into a shaker with ice & shake vigorously until well chilled. Strain into Martini glass & garnish with a single cherry (or, alternatively, a slice of lemon peel; flamed, if liked – presumably representing a ‘downed aviator’…).

I wasn’t taken by the results of this at all, which was a surprise. The proportions here create a drink with too acidic an attack from the lemon juice, which seems to linger in the back of the throat. I think the proportions are wrong, and would switch the amounts of maraschino & lemon juice around. But the drink is undeniably a pretty one, and may well appeal to Cosmopolitan drinkers who want something in a similar style, but less sweet. Classic recipes leave out the creme de violette, but it certainly gives the drink an attractive colour and an unusual flavour. It is worth tracking down.

Recipe notes: The sour base of this cocktail means that it features in quite a few variants. For example, drop the creme de violette in favour of a few drops of orange bitters, and this cocktail becomes a Casino.

Historical notes: The cocktail was invented by Hugo Esslin in New York, whilst working at the Hotel Wallick, and first recorded in his book, Recipes for Mixed Drinks in 1916. My facsimile copy of Craddock’s Savoy Cocktail Guide from the 1930s, includes the recipe, but as noted before, lacks the creme de violette.

The Aviation

Sazerac

One of the oldest cocktail recipes, the Sazerac is very simple: rye, sugar, Absinthe & Peychaud’s bitters. The bitters are very important here: it has to be Peychaud’s, otherwise you are not making a Sazerac. The correct recipe uses a large slice of lemon peel. Tonight, I am out of lemons, so have substituted a slice of orange peel; I quite like this, and find the flavours more mellow, and very similar to an Old-Fashioned. The lemon gives the drink more zip, but this evening I prefer it this way.

Proportions (using a jigger/pony measure):

1 jigger of rye (Canadian Club in this version)

1 small sugar cube or a pony of simple syrup

3 drops of Extreme d’Absente Absinthe bitters or a small quantity of Absinthe

4 drops of Peychaud’s bitters

Glass: Old Fashioned glass

Chill the glass. Muddle the sugar cube with the Extreme d’Absente bitters (if you are using regular Absinthe, then rinse the chilled glass with a few drops of the Absinthe and drain) in your mixing glass. Stir the whiskey together with the Peychaud’s bitters and ice into the sugar mix and strain into the chilled Old Fashioned glass. Garnish with a large slice of lemon peel (or orange, depending on the state of your fruit bowl).

Historical note: Louisiana’s Legislature adopted the Sazerac as New Orlean’s official cocktail on 23rd June 2008.

Update: I forgot to credit the redoubtable legendary barman, Brian Silva, for making the first Sazerac I tasted when he ran the cocktail bar at Rules Restaurant. He noticed I had been drinking a Manhattan previously, and suggested I might like to try the Sazerac as an alternative. He mixed it the ‘correct’ way – chilling the glass with ice, then rinsing it with a quantity of Absinthe, before building the rest of the drink. The results were sublime.

Further update: Brian Silva now runs the bar at Balthazar in London, and has written a book, which is highly recommended. You can read about his excellent career in an article in the Rake magazine.

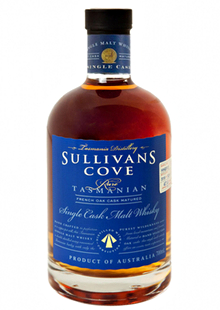

World’s best single malt is Tasmanian

An industry that wasn’t even legal until twenty-two years ago has carried off the top prize for single malts at this year’s World Whisky Awards, where the French Oak Cask-matured Sullivans was described by one of the judges as a ‘match made in heaven, with a smooth buttery feel’. Sullivans Cove distillery is located on the Australian island of Tasmania, about as far away from the spiritual home of whisky as one can imagine.

The Guardian newspaper despatched Vicky Frost to visit a nearby distillery, William McHenry & Sons, described (until someone works out how to distill from Antarctic glacier water) as the ‘southernmost distillery in the world, in a fascinating article, that can be read on the Guardian website. The island is now home to no less than nine distilleries, all benefitting from a change in the law that had, until twenty years ago, made distilling on Tasmania illegal for over 150 years.

However, chances of finding a bottle from the winning barrel must rank as somewhat slim; comments on the Guardian article suggest that only 556 bottles of this batch (HS52) were produced, selling for around £77 ($115) each. The batch has already been shipped, so the only bottles now available will already been on the shelves of the few number of places that stock Sullivans Cove worldwide. Good hunting.

(Update: a quick check on the Whisky Exchange shows that Sullivan’s single malt is out of stock.)

Bitters (3)

The bitters I have made from the ‘House’ recipe in Brad Parson’s Bitters book are now bottled and ready to use.

I was really pleased by the way my first attempt turned out: the sour cherries in the recipe have given the bitters a fantastic fruity kick, with vanilla and star anise notes from the spices. I would like to make the recipe a little stronger next time; perhaps I need to find a stronger alcohol base for the extraction in future.

I have bottled the bitters in some herbal remedy bottles that I picked up on my shopping trip to Baldwin’s, and these not only give the bitters a professional touch, but also make them easier to use. The design of the label is taken from the Periodic Table, and I took the idea of ‘Bt’ element name from the original ‘BTP House bitters’ recipe, in homage to Brad Parsons.

3-4 drops at a time of the bitters adds a fantastic depth of flavour to my drinks, and I have successfully used this recipe in my Manhattan and Old-Fashioned cocktails recently.

I am now thinking about the flavours I want to use in the next batch – perhaps using traditional English flavourings like sloes or similar.

Martini: Bombay Sapphire

Although I still think the Manhattan is my favourite cocktail, the close second has to be an ice-cold Martini. There is something about the sparseness of the ingredients and the purity in presentation that makes this a very elegant drink that delivers its alcohol kick with a degree of precision few drinks can match.

Although I still think the Manhattan is my favourite cocktail, the close second has to be an ice-cold Martini. There is something about the sparseness of the ingredients and the purity in presentation that makes this a very elegant drink that delivers its alcohol kick with a degree of precision few drinks can match.

I have seen opinions that state that Bombay Sapphire is too floral or delicate for a Martini, and that drier, more robust gins, such as Tanqueray or Gordon’s are necessary. I don’t agree, but perhaps my view is slightly skewed by my bottle of Sapphire being an export-strength version, found in Malaysia. The extra alcohol perhaps counteracts the floral notes of their recipe; either way, I find it makes for a very crisp and refreshing Martini. Exactly what one looks for in this drink I think.

One other small note: whatever you do, don’t omit the bitters. A few drops of something to add an extra dimension of flavour is really effective in this drink. Traditionally, a citrus-style bitters is recommended, like Fee’s Orange. This time, I used my batch of Brad Parson’s BTP bitters that I made last month. The sour cherry notes of those bitters worked really well here.

Update: another cause for debate here is the quantity of vermouth. I really don’t believe that refracting the light through a vermouth bottle into the shaker works, neither Noël Coward’s trick of nodding in the direction of Italy nor Churchill’s of looking in the direction of the vermouth bottle gives the required results. By all means, add smaller or larger quantities of vermouth, but it has to be there; otherwise you are just drinking a glass of gin with an olive in it. That is not a cocktail. And it is the flavouring of the vermouth that modifies the gin into the Martini.

I stir my Martinis; for a debate on them whys and wherefores of the stirred/shaken debate, please take a look at my earlier post here. I just think the lack of ice shards in the drink, and the clarity of the liquid that results from a careful stirring gives for a better end result.

Proportions (using a jigger/pony measure):

1 jigger of Bombay Sapphire gin

1 pony of Noilly Prat vermouth

3 drops BTP ‘House’ bitters

Glass: 3oz Martini glass

The method is similar to the Vodka Martini I made earlier:

Stir vermouth together with ice in a Boston shaker jar and tip away around half the vermouth. Add the gin, drops of bitters & stir again. Pour into a chilled Martini glass & garnish with a green olive, stone-in.

Shaken or stirred?

Entering into the shaken versus stirred debate with a cocktail purist without some prior preparation is much like making a Martini without preparation; the results are going to be disappointing for everyone.

The debate seems to have been around for ever, and to summarise the positions: the general theory is that shaking a drink results in a wildly different experience to stirring the same mixture, and that there are inherent superiorities in either method, depending on one’s particular views.

In popular culture, the starting point for all of this seems to be the famous request by James Bond for his Vodka Martini to be, ‘Shaken, not stirred’ (a quote wonderfully undermined in the re-boot of Casino Royale when an unhappy Bond snaps at the bartender’s query as to which way he wants his drink made with an angry, ‘Do I look like a give a damn?’). Since then, the shaken Martini has appeared cooler than the pedestrian stirred variety.

But the arguments for both sides have a few more planks than this, to wit:

• Shaking a Dry Martini produces a drink that is technically no longer a Martini; it becomes a Bradford. In reality, no-one I know uses the Bradford name any more, except perhaps scoring points for obscure knowledge.

• Shaking is a more brutal environment for the ice. Tiny fragments shatter off the cubes, resulting in lots of little pieces of ice in the drink. To some purists, this pollutes the drink; to others this creates a more refreshing, colder drink, with less water in the mix (the action of melting the ice during the mix means that up to a quarter of a Martini can be water (source: Rob Cassels, The Cocktail Keys).

• Stirring a drink is a gentler process, resulting in a drink that retains its clarity, whilst not being cooled to such an extent. A graphic example of this can be seen in Manhattan: Rye recipe versus my Manhattan: Bourbon recipe; I stirred the Rye-based drink, but shook the Bourbon – one can see the difference in appearance immediately.

• Some arguments are that the shaking bruises the gin/vodka/vermouth or whatever. I doubt this really means anything, but what shaking will do is introduce lots of little air bubbles into the mix, and much like letting a bottle of wine ‘breathe’ after opening, the act of letting air into a mixture can dramatically change the flavour of a drink.

Simple taste tests suggest that there is a point; a shaken Martini does taste different to a stirred one. Back in 2006, the LeisureGuy blog followed up on research in the New Scientist, which carried out a taste test on two Vodka Martinis, one using a potato-based vodka, the other with a grain-based spirit, and found there was a discernible taste difference between the two spirits. And going further than this, the British Medical Journal has published a paper (BMJ 1999;319:1600) that studied the antioxidant effect of Martinis, as a result of their preparation method. Their conclusion? Shaking a Martini resulted in a lower proportion of Hydrogen Peroxide in the finished drink. Perhaps Bond was a health nut after all – he was famously sent to a health farm to recover & told Moneypenny that he was ‘On a mission to eliminate all free radicals’.

Fundamentally, the decision to reach for the shaker or the bar spoon will depend on one’s personal tastes. But a few points of my own:

• Stirring a Martini results in a clearer drink, but one that is not as cold as the shaken variety.

• A Vodka Martini tastes better to me when shaken, rather than stirred. The extra cooling action of the shaking seems to take the edge of the vodka. The notable exception to this rule is my experimentation with the Black Cow Vodka Martini recently; that tasted fine when stirred, but I had chilled the vodka in the ‘fridge before mixing.

• A Martini (i.e. made with gin) tastes discernibly better when stirred, not shaken. I do not like my gin cooled too much, and the mellower cooling of stirring seems to suit me better.

The Martini

Leisure Guy’s selfless testing of potato versus grain vodkas, and their effect on Vodka Martinis…

The Martini is among the best of cocktails, if not the best. (Cocktails, unlike highballs, are undiluted with water, juice, soda, etc.)

The Martini was so popular and well-known that Ian Fleming, to characterize James Bond as a person who flouted convention, had him favor a vodka Martini (a true Martini uses gin) and had it “shaken, not stirred.” Unfortunately, the “shaken, not stirred” line lived on in the public mind as Martini knowledge waned, so that today some believe that the Martini is supposed to be shaken and not stirred, a major mistake: if you use the Martini ingredients and shake rather than stir, you get not a Martini, but a Bradford, a drink that resembles the Martini except that it’s polluted with tiny ice chips that melt rapidly and dilute the taste.

UPDATE: The above paragraph is wrong, alas. Here’s the true reason why Bond wanted a (vodka)…

View original post 793 more words